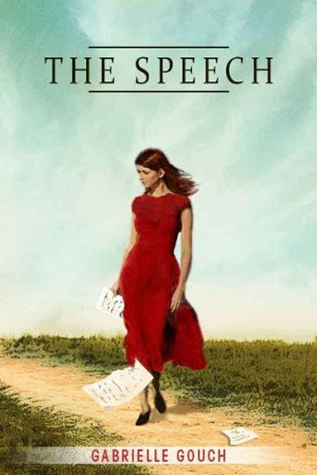

The Speech

Inspired by the life of a real person, this is a story of brilliance and insanity and how one man’s fate impacts on three generations. A tale of love and loss set against the background of politics and the machinations of bureaucracy.

Clara, a naïve young woman, leaves her native Amsterdam to live with Peter in Australia. They are happy, but slowly, imperceptibly, change creeps in. It builds up, their love turns to ruins.

Separated and with a young daughter who adores her father, Clara is faced with agonizing choices. The contrast between her personal struggles and the concerns of the people around her – career bureaucrats who design services for the vulnerable – could not be more farcical.

How does Clara navigate through her web of circumstance? What happens when her decisions escape from the personal and become wide-ranging?

A thought-provoking story about people facing complex moral dilemmas.

The book is available from Amazon

Some Goodreads Reviews

Gabrielle Gouch positions herself as one of Australia’s finest authors with this exquisite and sensitive novel. Concealed beneath its engaging storyline lies a subtle expose of the public sector’s administration of vulnerable people. Her prose is a pleasure to read, quickening the senses so that the reader is transported through time and space.

Anita O’Toole

This is a fascinating, and sometimes unsettling novel about a young woman’s journey through life’s unexpected and at times heart-breaking phases. The story will stay with me for a long time.

Maria Gal

The story is brilliantly written. It is elegantly dealing with a myriad of emotions happiness, sadness, hopefulness, loneliness and helplessness of the main character of the story. In addition it describes vividly the dark and painful issues of mental disease, the effect on the person affected by it as well as the pain of the family.

Tuvia Chaki

Although the story is Australian, it is universal and thought-provoking. It is superbly written.

Yossi Leitner

Read an extract

Ten years ago her life couldn’t have been more different. Ten years ago she was living on the other side of the globe, in her native Amsterdam, the city she cycled through most days and knew well enough to be a guide. She knew where the best croquettes and the tastiest herrings were sold. She knew the cheapest cafes where one could sit with friends and talk for hours. She knew where the theatres, the best bookshops and libraries were. At the time Australia couldn’t have been further from her mind. A continent on the map, a country in the Southern Hemisphere, not a country she knew much about, or was interested in. Not until that early April morning in 1988.

She was standing at the window, looking at the grey cloud sagging over the city, over the sticky wet cold. Below, in the narrow street, the breeze churned the puddles between the cobblestones and the reflections of the streetlights still on. The street was waking. Opposite, two shops had thrown their doors open. People, umbrellas, walked past.

It had been a long winter and spring was late to arrive. She stood there thinking that it would be a cold rainy day again, a day of long sleeves and jumper and coat and heavy shoes.

She longed for summer. She longed for sunshine and light clothes and bare arms and trips with her friends cycling through the fields of tulips and green land. And laughter and startled birds whooshing past.

The phone rang.

‘Father, are you at work already?’

‘Just got here. Clara, make sure to wrap up warm, it’s cold out there.’

She smiled. He’s mothering me again. She was used to him worrying about her, used to his caring words, which like a warm cocoon had enveloped her ever since she could remember.

‘By the way, there’s been a change in my conference schedule,’ he said. ‘One of the moderators is in hospital and I’ve been asked to stand in for him. Sorry, but I’ll have to leave next Monday.

‘More freedom for me,’ she laughed.

‘Clara, make a list with all the things you’ll have to take to Dafna, so you won’t have to rush back and forth like you did last time.’

‘I’m not moving to Aunt Dafna’s again. I’m staying put.’

‘I don’t like you being on your own every evening.’

‘But father, I’m twenty-two years old. Twenty-two, remember? I don’t need babysitting. My nomadic days are over,’ she said and held her breath.

The line was silent.

‘Ok,’ he said at last, ‘but promise me that you’ll ring her every day and go for dinner every now and then.’

‘I will. So have I come of age finally?’ She laughed. ‘How about a celebration before you go?

‘This Friday?’

‘It’s a date.’

My coming of age. She smiled to herself and began packing her backpack. Coat on, she picked up the umbrella and opened the door. And there it was again, the putrid smell, the smell of witches’ brew to entice back the departed. She rarely got angry, but now she was furious and headed to old Mrs Jansen’s door across the landing. After the third ring, the door opened and in front of her stood a young man she had never seen before. He looked at her questioningly. Mrs Jansen was out and he was from Australia, a friend of her friend.

A tourist in shirt and pressed trousers? Well, it takes all sorts.